The Big Finish

No – this isn’t my my Big Finish – as in my last blog. Well, at least I hope it’s not my last blog. If it is, then I’ve got bigger problems to deal with.

No – this isn’t my my Big Finish – as in my last blog. Well, at least I hope it’s not my last blog. If it is, then I’ve got bigger problems to deal with.

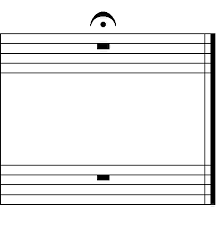

This is about endings. Specifically – musical endings. The old “double bar line.” How we conclude our arrangements. Because let’s face it – starting a new arrangement is always easier than finishing it.

If you are like most arrangers, you are already writing the modulation into the 3rd chorus before you ask yourself, “How am I gonna finish this thing?” And if, like me, you loathe repeating yourself, you might also be wondering, “How can I end this differently than my last ten pieces?” Worse still, if you are obstinately determined to NOT be like all the other arrangers, you might be asking, “How can I end this without sounding like everybody else?”

To answer these daunting questions, I will offer: There are no easy answers. (Total cop out, I know.)

If you’ve written more than twenty arrangements for any particular musical ensemble (choir, orchestra, band, etc.), chances are you’ve already begun to mimic your prior endings. And if you write for the church in particular, where big endings are by far the norm, chances are higher that you’ve repeated yourself. Multiple times.

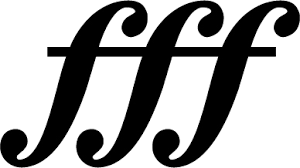

About those big endings: There is nothing inherently wrong with a big ending. Big endings work great much of the time. But I would guesstimate that about 80% of church choral music ends BIG, which makes it predictable and (Dare I say?) boring. I don’t know whom to credit or blame for this phenomenon. I’ve done no historical research, but it’s been going on for as long as I’ve been in the profession. Maybe it’s our church culture. I’ve been told of one mega-church pastor who insists every choir anthem every Sunday ends big, so that he can stride Caesar-esque to the podium accompanied by clashing cymbals and flourishing brass. So maybe it’s that guy’s fault. Or the fault of the seminary that taught him that good preaching must be introduced with a fanfare.

About those big endings: There is nothing inherently wrong with a big ending. Big endings work great much of the time. But I would guesstimate that about 80% of church choral music ends BIG, which makes it predictable and (Dare I say?) boring. I don’t know whom to credit or blame for this phenomenon. I’ve done no historical research, but it’s been going on for as long as I’ve been in the profession. Maybe it’s our church culture. I’ve been told of one mega-church pastor who insists every choir anthem every Sunday ends big, so that he can stride Caesar-esque to the podium accompanied by clashing cymbals and flourishing brass. So maybe it’s that guy’s fault. Or the fault of the seminary that taught him that good preaching must be introduced with a fanfare.

Regardless – I’m assuming big endings are here to stay. I’ve written more than most of you – so if there’s a problem I’m part of it. But being the troublesome sort, who feels compelled to be different (Ask any of my publishers), I have written lots of quiet endings for pieces that could have just as easily ended big. And I often did this simply because everybody else was writing big endings. The sad truth is, these quiet endings may well have cost me sales – because (if my own catalog is any indication) big endings tend to sell more music.

So it’s the market’s fault then.

Regardless – there is the whole Big versus Small ending question you have to decide. But even after that, it seems there are limited ways to end a piece Big or Small.

True story: Years ago, I was in the middle of a choral project for Word Music. I was aware that I was repeating myself in the endings of a couple of the charts. I asked an arranger buddy (a guy with more experience than me by far) if he ever repeated himself when ending a chart. He casually replied, “I’ve repeated myself so many times, I’ve numbered my endings. On any given chart, I’ll just decide, ‘This one is a #8 or a #17.'”

My friend was kidding. (At least I think he was.) But the point was made. You crank out enough music, you’re gonna duplicate yourself at some point.

So what’s my sage advice here? (Not that there ever was any to begin with) I’ll sum up in a list, because lists are popular and overused much the same as Big Endings.

- Don’t assume everything you write needs a Big Ending.

- Don’t assume Big Endings are bad.

- Stop assuming, in general. It will make you a more creative thinker.

- Try to come up a new way to finish your current piece that doesn’t sound just like the last four pieces you wrote.

- Despite what the mega-church preacher thinks, a quiet ending can sometimes speak louder than a bombastic finale.

Leave a Reply

Recent Posts

Recent Products

-

Revive Us Again

$1.29 – $79.00Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Praise to the Lord, the Almighty

$1.29 – $79.00Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Sweet Hour of Prayer

$1.29 – $79.00Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Poor Wayfaring Stranger

$1.29 – $79.00Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page

Sign up for our Newsletter

Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit